What Does “Core Engagement” Actually Mean?

Much like how our mid section feels before being told to “engage,” the core is loosely defined and there isn’t a consensus on what the core even is. Despite this, we hear a variation of “engage/tighten your core” all the time and across many athletic disciplines. But what does that even mean?!

While I don’t have the power to establish a well defined, globally accepted definition, I think it’s worth attempting to create a version that most people can utilize so the next time your instructor says “engage your core,” you’ll have a better idea of what to actually do.

First, let’s get a deeper understanding of the muscles you’re supposed to be using…

Abs vs Core

I think part of the confusion stems from “core” and “abdominals” being used interchangeably. Maybe upon reading the title you even thought, “duh, your core is your abs and you just squeeze them.” Well… that’s not the whole picture.

Your abdominals are a PART of your core.

Colloquially, fitness instructors and athletic coaches use the term “core” and “abdominals” interchangeably (including myself *slaps wrist*). It’s important that we do make the distinction between them though because it’s this ambiguity that creates confusion about how to utilize them and if we’re doing so correctly.

So let’s break it down…

Abdominal Muscles:

Unlike the core, the abdominal muscles are explicitly comprised of:

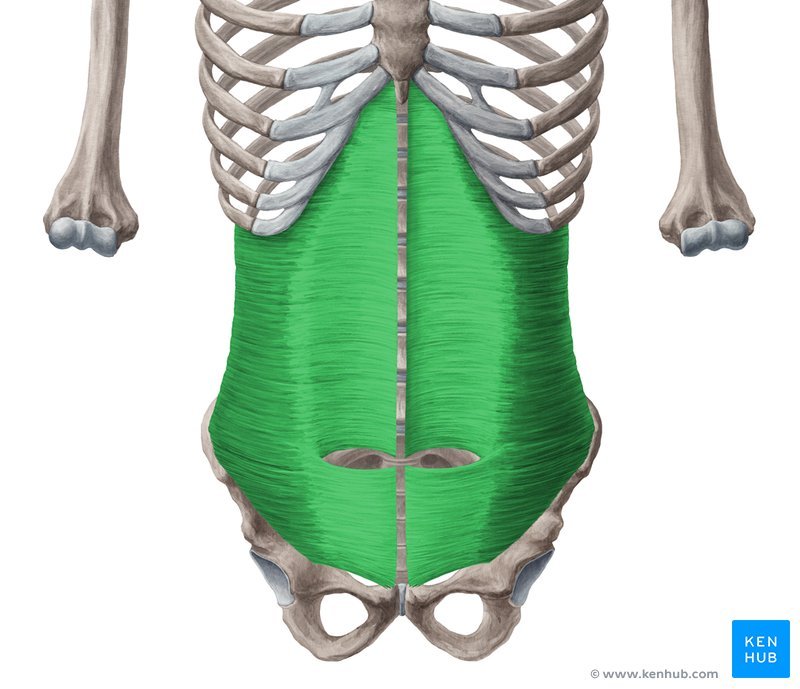

Rectus abdominis

The “6 pack” muscle that lays across the front of the trunk from the sternum down to the pubis bone (front of the pelvis). They help to flex the trunk (i.e. crunch), tense the anterior wall of the abdomen (to compress and protect internal organs), and posteriorly tilts the pelvis.

Internal Obliques

Lay obliquely (hence the name) from the lower 4 ribs down around to the iliac crest (top of the hip bone). They help to create intra-abdominal pressure (helpful in forceful expiration and coughing), as well as lateral flexion and rotation of the trunk (i.e. side bends and twists).

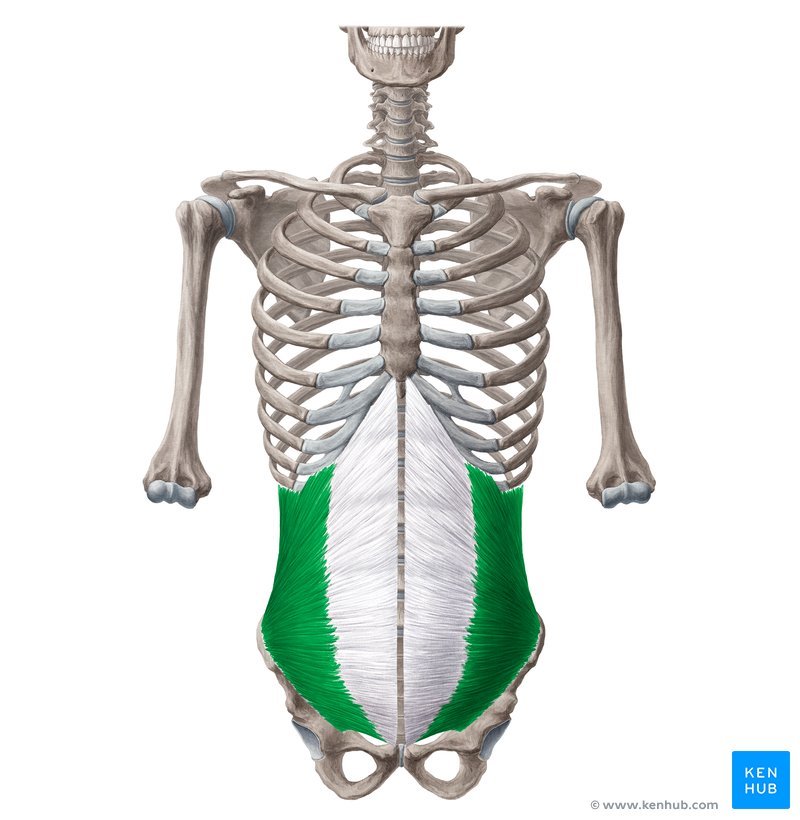

External Obliques

One of the outermost ab muscles, extending from the lower portion of the ribs around and down to the pelvis. They help stabilize during trunk rotation and flexion (i.e. twists, crunches, and side bends)

Transversus Abdominis

The deepest of the ab muscles, extending between the ribs and pelvis and wrapping around the trunk from front to backThey help to increase intra-abdominal pressure, support the lower spine and pelvis, and stabilize unilateral actions involving trunk rotation.

*The pyramidalis is also a very small abdominal muscle attached to the pubic bone. It’s only present in about 80% of humans and may be absent on just one or both sides (which is probably why you haven’t heard of it and also why I won’t be mentioning it outside of this post).

Core Muscles:

As mentioned earlier, there is no one consensus on what muscles are involved in the “core” but I’ll do my best to give you an idea of what muscles should be considered when addressing core strength and stability.

In addition to the abdominal muscles (detailed above) the core also consists of:

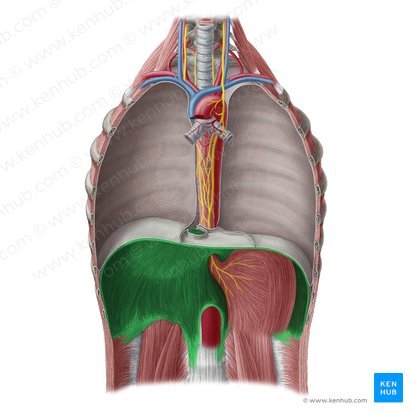

Diaphragm

A dome shaped muscle that surrounds the inside of the ribcage and increases abdominal pressure.

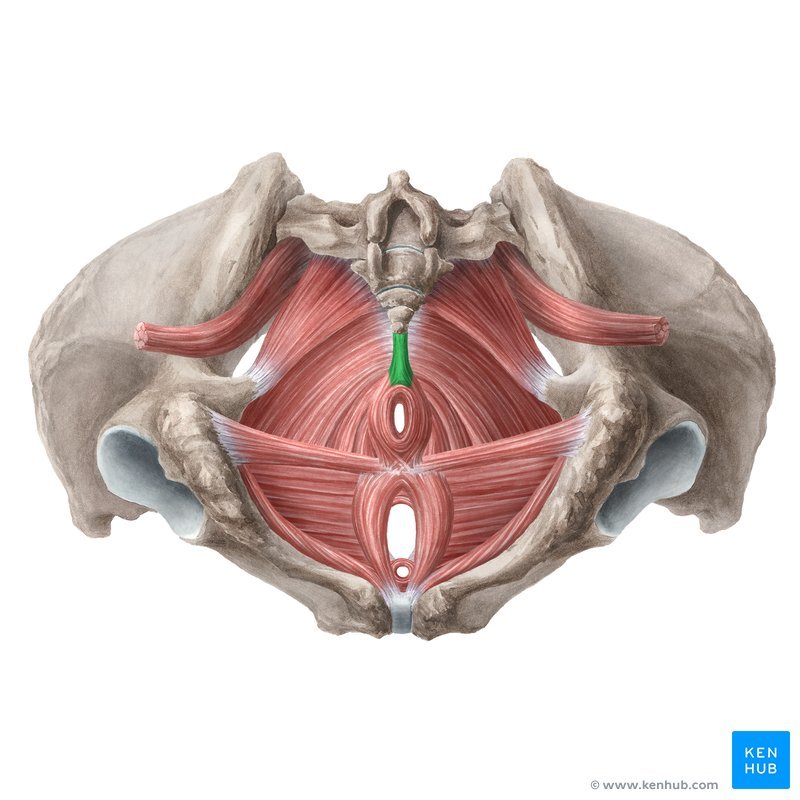

Pelvic floor muscles

A group of muscles that sit inside the pelvis and help to stabilize and support your lower internal organs and the trunk in tandem with other muscles of the core.

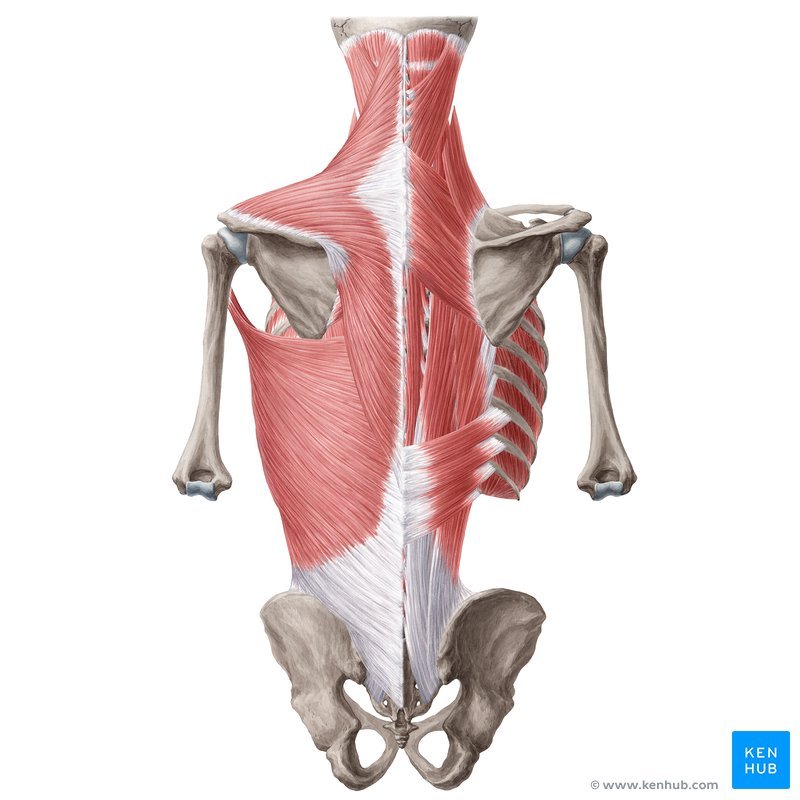

Back muscles

Particularly the lumbar multifidus, quadratus lumborum, erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, and serratus, these muscles help to stabilize the spine, rib cage, and pelvis.

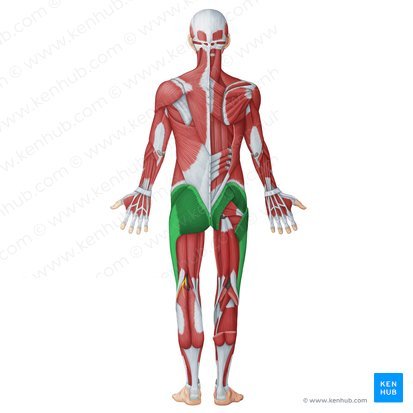

Gluteal and abductor muscles

To put it simply, the muscles that make up your butt and outer hips. They help to stabilize when on one leg and well as general pelvic and lower back stability.

How can we define the core?

There does seem to be one common thread that would tie all of these muscles into one unit that could explain what the core is…

they all help to stabilize the trunk (a.k.a. torso)

So, maybe a more accurate and helpful description/definition of the “core” is:

“The muscles that stabilize the trunk, particularly in the lumbar and pelvic regions.”

Is it perfect? No. But it’s a helpful starting point!

How do we “engage our core”?

This depends on why you’re engaging it — or, in other words, what action are you trying to produce or prevent. There is no one way to engage your core, so let’s go over some different methods that will help you utilize the above muscles during various movements and create a deeper mind-muscle connection to your core:

Bracing (a.k.a. isometric contraction)

Bracing your core will create intra-abdominal pressure by contracting your diaphragm, abdominals, pelvic floor muscles, and certain back muscles. This can also be done while isolating one region (i.e. kegels —contracting just the pelvic floor) or all at once, as shown here:

Stomach Vacuum (a.k.a. sucking in)

This move can be helpful if you’re someone who tends to push their stomach out while performing abdominal exercises or anteriorly tilt your pelvis, creating an exaggerated lower back arch during exercise or movement.

Trunk Rotations (a.k.a. do the twist)

We don’t live in just one plane of motion, so we need to be ready for movements that are not simply facing forward. There are numerous different rotational exercises to choose from, but here is a simple and effective one:

Proprioceptive Exercises (a.k.a. get unbalanced)

Similarly, we want to be able to maintain stability when placed in unstable environments or when performing movements that could throw us off balance. These exercises can be taken to the extreme and often do more harm than good (looking at you bosu ball fanatics), so keep it simple and try a proprioceptive exercise like this:

Does it even matter if my core is engaged?

Well… yes. But not all the time and not always through focused, concentrated effort.

Often in training we’re preparing our bodies for a specific movement or action, whether that's for sport or daily life. It makes sense then that during training, we will need to focus our mental energy on the muscles we are trying to strengthen whereas, throughout most activities and daily life, there shouldn’t be a huge, conscious effort to always have your core engaged.

By including focused core training, we are creating muscle memory so that the next time we have to perform a certain task or activity, our muscles more automatically (or with little conscious effort) brace, engage, contract, or expand in ways that support and stabilize our entire system and reducing risk of injury.

At first you may want to continue to place a more conscious effort during everyday tasks but overtime the goal is for your body to learn and take over that role.

Still not sure if you’re “engaging your core” or looking to add in more core training to your routine?

Core training is just one aspect of Mvmnt Method, a cross-training program for athletes, performers, and active bodies (a.k.a. YOU) to enhance performance and keep doing what they love for longer.

Schedule a FREE 30min consultation to see if Mvmnt Method is a good fit for your training needs!

Sources:

https://www.physio-pedia.com/home/

https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/education/the-human-anatomy